How we assess the CDR effect of an EW experiment

The basic concept of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) by EW as a solution to the climate crisis is: Cations from rock dissolving on agricultural lands accompany and balance bicarbonate ions in the soil water (=carbon capture), ultimately transporting carbon from the atmosphere to the ocean (=carbon storage). In our experiments, we wanted to measure this process by tracking the carbon transported as bicarbonate in the water leaching through the rock-soil mixtures.

Whereas direct measurement of bicarbonate is challenging, one can easily quantify alkalinity - which is largely made up of bicarbonate for close to neutral pH - through titration. Alkalinity can thus be used as a proxy for bicarbonate content. Our hypothesis is that we will only achieve significant gigatonne CDR through EW at a climate crisis relevant level and speed (resulting in trustworthy carbon credits), if we see at least some statistically significant relative increase or ‘delta’ in accumulated alkalinity export (i.e. the cumulative sum of titrated alkalinity measurements in mol/m² over time) between treated and untreated experiments in the first 12-24 months after the rock dust amendment. We believe that if an alkalinity increase in the leachate water takes more than 2 years to show up in our greenhouse experiments, it will be more difficult to accurately measure and timely quantify a weathering signal for a similar rock-soil combination in an outdoor EW project based on this. In turn, this will make it more difficult to create and sell carbon removal certificates based on the EW process to refinance the effort and is thus too slow to help us fight the climate crisis.

We are therefore using alkalinity measurements comparing treated and untreated pot experiments to measure the CDR effect of a rock dust addition to a specific soil. For our experiments we defined the CDR effect over time as the increase in accumulated alkalinity (pot surface area corrected, in mmol/m²) in the leachate water of a treated pot compared to its respective control. When assessing this CDR effect, the mineralogy of the rock also needs to be taken into account (e.g. primary and secondary minerals, including carbonates). We acknowledge that there are other potential pathways of CDR by EW (e.g. stabilization of organic matter, formation of secondary carbonate minerals), but these pathways are not considered in this document, as they were not part of the design and execution of our experiments and we have no related soil data yet.

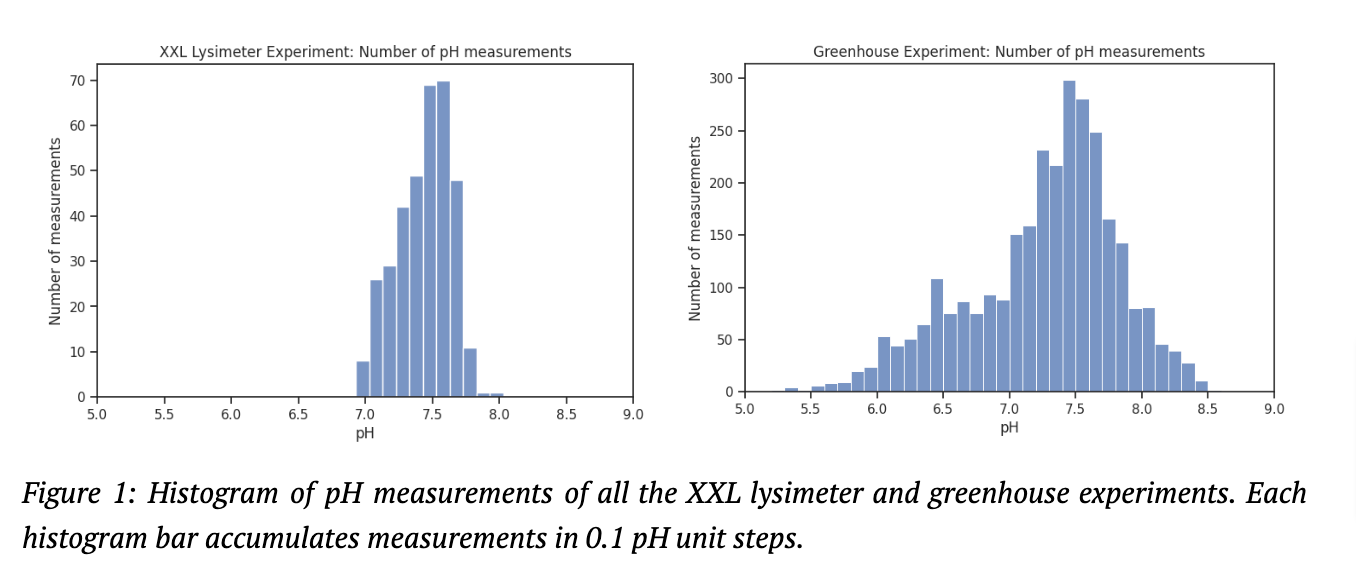

We have written extensively about our alkalinity based CDR assessment in our paper “CDR Measurement for ERW via Alkalinity in Leachate” and added a “Deep Dive: Why measuring alkalinity is not the same as quantifying HCO₃⁻” a few months ago. There we argue that “Only at a soil water pH 6.5-8 is the DIC mainly present as bicarbonate anions and one could assume the carbonate system to be made up of only HCO₃⁻. “ Most of our leachate measurements were in this pH range, see figure 1.

In our experiments we have found some EW experiments that demonstrated a CDR effect in the form of increased alkalinity export within the first 2 years, while in others we could not detect such a CDR effect. Now we can delve into the differences between the experiments to find clues about what to do and what not to do when designing CDR projects. And there is still the possibility that the released cations from the alkaline materials (which we expected to see after a breakthrough in the leachate water along with the captured carbon in the form of bicarbonates) will sooner or later be sequestering carbon. To be clear, we do not expect the now captured/parked cations soon, but those newly released ones passing by as they cannot park.

In addition, some released cations, trapped in the soil by storage mechanisms, might still be released if physicochemical conditions change with time. Some cations might be stored long-term into precipitates of secondary clays, oxides, etc. (see Te Pas et al. (2024)). The potential role of combined microbiological processes affecting time dependent realisation of alkalinity based CDR is still under researched, and may need more attention.

In order to scale-up the EW industry, we need to find out IF our measurements actually reflect the CDR and WHAT makes certain soils and rocks such unexpectedly poor options for CDR and use this data to make CDR predictions, so that we can avoid similar situations in the future. For the time being, our rather random choice of soils from Germany does not look very promising for CDR for the used low reactive alkaline materials. Perhaps these nutrient rich soils in temperate climates are not the first choice for EW projects, and more depleted soils in the humid tropics should be prioritised. On the other hand, consequences of using more reactive alkaline materials like steel slag on soil functions should be assessed, to avoid possible negative consequences due to too rapid soil biogeochemical changes.

Ultimately, the results of our experiment reflect what we have already pointed out in our article about the stages of measurement for MRV: for a reliable MRV (monitoring, reporting and verification) methodology, it is necessary to consider all 4 stages of the CDR-through-EW process.

The voluntary carbon market has yet to standardize a method to handle unique EW traits of CDR performance, such as cation migration and retarded alkalinity transport to stable storage reservoirs. The work presented in this study confirms the very real and measurable effects of these soil-based processes that should be carefully considered prior to issuing claims-based CDR.

If you want to dive deeper into this, please read our extensive whitepaper report What We Learned from the World’s Largest Greenhouse Experiment.